Manufacturing Development:

A Strategy for Small-Scale Manufacturing

in Newfoundland and Labrador

May 1999

Message from the Minister

It gives me great pleasure to provide you with Manufacturing Development: A Strategy for Small Scale Manufacturing in Newfoundland and Labrador. This document outlines a dynamic new approach to Government=s support for the small scale manufacturing sector. It is a strategically important aspect of Government=s overall jobs and growth agenda.

We are focussing on small scale manufacturing as it is a propulsive sector of our economy holds opportunity for all parts of our province, particularly rural areas, and can provide year-round stable employment for our people.

Development of this strategy has been a team effort, with extensive consultations involving provincial and federal government departments, industry, education and training institutions, and community based economic development organizations. The Strategies for Action contained in this document represent a consensus of all key stakeholders as to how we can best support the growth and diversification of small scale manufacturing enterprises in our province.

I look forward to working with our partner agencies, industry and other groups as we move ahead with implementation of this strategy.

Beaton Tulk

Minister for Development and Rural Renewal

EXECUTIVE SUMMARY

Manufacturing has undergone significant change in an era of global competition, new information and production technologies and corporate re-structuring. Increasingly, small scale manufacturers are able to compete in specialized market niches or in the production of inputs required by larger firms. While many large manufacturers have downsized in recent years, they have created opportunities for small scale manufacturers by out-sourcing much of what used to be done within one factory. Firms located in peripheral regions such as Newfoundland and Labrador have opportunities to compete successfully in this environment, if they adopt emerging

Abest practices@ in manufacturing. Similarly, governments, industry associations and community development organizations which hope to foster manufacturing development must understand these trends and learn what approaches to sector development offer the greatest chances of success.

The Small Scale Manufacturing Strategy for Newfoundland and Labrador presents lessons on best practices and the approaches necessary to maximize sector development in this province. It has been developed in cooperation with the Alliance of Manufacturers and Exporters Newfoundland (the Alliance), the federal government, the Faculty of Engineering at Memorial University of Newfoundland and the Bishops Falls Development Corporation. It has involved original research on global trends and approaches to sector development in nine jurisdictions in North America and across the North Atlantic Rim and, in cooperation with the North Atlantic Islands Program, has carried out detailed interviews with sixty small scale manufacturers in Newfoundland and Labrador, Prince Edward Island, Iceland and the Isle of Man.

The findings from this research reveal that in an era of global competition small scale manufacturers must focus on what they do best - their

Acore competencies@ - and learn to market their production effectively to maximize sales. They must seek out information on new production and marketing techniques by Abenchmarking@ themselves against other firms. They must adopt a commitment to quality processes which monitor and meet customer needs in all aspects of production and sales. As they focus on their area of core competence, they must practice flexible manufacturing, so that every opportunity to apply their competitive advantage is exploited. With increased opportunities through out-sourcing by other firms, small scale manufacturers must learn to work with other firms in business networks and learn how to manage their place in the supply chain by adopting quality certification procedures, utilizing information technology and mastering transportation logistics so they can deliver Ajust-in-time.@ Firms which adopt these practices export more, grow faster and sell more than small scale manufacturers which remain Ageneralists@ by producing a range of products without focusing on what they do best.

For governments, industry associations and community development organizations seeking to foster manufacturing sector development, the comparison with other peripheral regions, provinces, and countries, also reveals Abest practices.@ Applying lessons from one location to another must take into account the significant differences which exist in creating a supportive socio-economic environment. The ability to tailor fiscal, monetary and trade policies to the needs of sector development in a region varies significantly from provinces like Newfoundland and Labrador to countries like Iceland and Ireland. Whatever the nature of the jurisdiction, however, a key lesson for sector development is the ability to take a coordinated and sustained approach to manufacturing development. Those places which marshal available resources for human resource development, infrastructure supports and business development in a coordinated, systematic manner for a sustained period of time greatly increase the chances of success in expanding the sector. This is enhanced by taking a strategic approach which identifies local strengths and external opportunities and targets specific sectors matching the region=s comparative advantages. To implement such strategies, governments must enter partnerships with industry, communities, education and training institutions and other stakeholders. Wherever there are individuals or groups which are Achampions@ for sector development in a region, they must be encouraged and supported. Finally, business supports must be available which address the best practices for small scale manufacturers.

TABLE OF CONTENTSFive key areas of Strategic Action are identified to apply these lessons in Newfoundland and Labrador. The first requirement for sector development is to openly recognize small scale manufacturing as a development priority. Secondly, information and education on the best practices and approaches outlined in the strategy need to be communicated to stakeholders throughout the province. Third, supports will be targeted to implement best practices through government programs, the Alliance, Memorial University of Newfoundland, the College of the North Atlantic and Regional Economic Development Boards (REDBs). Fourth, a strategic approach must be taken to build on strengths and opportunities in working with existing firms and in investment attraction efforts. Finally, a Manufacturers Development Forum needs to be established to coordinate and sustain the implementation of this strategy through a partnership of governments, industry and education and training institutions. Partnerships also need to be fostered with REDBs, organized labour and municipalities, to ensure that a supportive environment is fostered for sector development.

By implementing these Strategic Actions in a sustained and coordinated manner, small scale manufacturers in Newfoundland and Labrador will be able to operate in an environment which enhances their efforts individually and collectively. Governments, industry associations, education and training institutions and community-based organizations should focus their efforts to support the adoption of best practices. The human resources, technology, business supports and infrastructure required for firms to flourish within the sector need to be identified and supported to make maximum use of available resources. New firm creation and the attraction of firms from outside the province should be based upon an understanding of what our competitive strengths are and where existing gaps can utilize new investment, technology and know-how. The end result will be enhanced diversification of the economy in all areas of the province and the creation of sustainable employment for Newfoundlanders and Labradorians.

1.0 Introduction

2.0 Methodology

2.1 Global Trends Study

2.2 Case Studies

2.3 Development Support Study

3.0 Study Findings2.3.1. Jurisdictional Profiles

2.3.2 Baseline Indicators

2.3.3 Development Support Environment

3.1 Global Trends

3.2 Case Studies

3.3 Development Support Study3.3.1 Jurisdictional Profiles

3.3.2 Development Support EnvironmentSupportive Socio-Economic Environment

Coordinated and Sustained Commitment to Sector Development

Strategic Approach

Partnerships and Champions for Implementation

Business Supports for Best Practices

Business Financing

Incentives

Business Operations

Business Networks

4.0 Conclusion

Appendix I - Small Scale Manufacturing Study Advisory Group Participants

Appendix II - Development Support Study Jurisdictional Liaisons

Appendix III - GUIDELINES FOR ENTERPRISE INTERVIEWS

IV - BIBLIOGRAPHY

1.0 Introduction

Since the industrial revolution, manufacturing has helped define economic development. Manufacturing is the process of taking resources and through packaging, processing, fabrication and/or assembly transforming the resources to a physical product demanded in the marketplace. In peripheral areas, manufacturing has consisted primarily of processing raw resources into semi-processed goods. These goods are then further processed into products. The additional processing usually takes place in areas close to the marketplace resulting in a clustering of the required technology, capital, services, management and workforce. Over time this centralization of value added production made regions with large urban populations strong in manufacturing development while peripheral areas remained dependent on primary resource production.

Since the 1950s, some opportunities rose for peripheral areas to attract

Abranch plant@ production. This did not occur until decentralized production was made possible through the development of standardized manufacturing processes that could be applied to mature products. Branch plants, as a rule, located where expenses were minimal and the regulatory environment was less restrictive. These plants provided some employment but few of the higher value activities associated with manufacturing development and were always vulnerable to closure when more attractive, lower cost sites were available. As such, throughout recent history, efforts to transplant large-scale manufacturing with branch plant attraction efforts seldom succeeded. The absence in peripheral areas of the supportive network of related suppliers, specialized infrastructure and experienced management and labour also made successful transplants the exception rather than the rule.

For jurisdictions such as Newfoundland and Labrador efforts were made to promote large scale manufacturing. The promotion of manufacturing to support regional development is understandable as it is clearly a

Apropulsive@ sector for any economy. Manufacturing usually creates well-paid, year-round employment which then increases economic activity through consumer spending. Manufacturing transmits wealth throughout the economy by encouraging up- and downstream production linkages, consisting of opportunities to produce inputs used in the manufacturing process (upstream) and to use the outputs for further manufacturing (downstream). Inputs can be primary resources or goods produced by other firms. Inputs can also be services in transportation, communications, enabling technology, accounting or any number of supports required for production. In addition, outputs of one manufacturer can become inputs for further production by other manufacturers ( eg. plastic bottles as inputs for bottled, flavoured iceberg water). There are examples of successful large scale manufacturing in Newfoundland and Labrador, but there have been significant changes in the nature of manufacturing production which point to new opportunities for smaller manufacturers as well.The changes that are now providing opportunities for small manufacturers began in the 1970s and were characterized initially by a decline in large scale manufacturing employment in major urban centres as well as growth in the service sector. Some of the decline resulted from technological innovations that allowed productivity to increase while employment levels decreased. Much of the decline, though, occurred when in-house support service activities within manufacturing firms were outsourced to companies with the specific skills needed to satisfy the needs of the manufactures. This outsourcing of the 1970s is no longer limited to the service sector. Now large manufacturers are outsourcing specialized activities to smaller firms who have the special skills and capabilities to deliver products once produced in-house.

As these new opportunities were emerging, many peripheral regions started to look towards other sectors as the basis for development. Globally, in the 1980s, increased attention was focussed on the emergence of a post-industrial

Ainformation age@ economy. This Anew economy@ was driven by information technology and knowledge-based workers, not the industrial activity and factory workers traditionally associated with manufacturing. Some, peripheral regions felt they could Aleapfrog@ the industrial age into the Anew economy@ defined by the production of knowledge based products rather than manufactured goods. Development efforts focussed on ways to harness new information and communications technologies to foster growth in business services.What is now increasingly apparent is that small scale manufacturing is part of the

Anew economy@. Market and technological forces have influenced operational, location and market decisions, and specialized small manufacturers are dealing with more knowledgeable and demanding clients who can compare local firms with those in other countries. New technologies are changing the scale and scope of manufacturing production. Some production of low cost, standardized, goods continues where low cost labour and few regulations apply. Increasingly, however, small batch production of sophisticated goods characterizes manufacturing which, with new technologies and production processes, can often be carried out in peripheral areas by small and medium sized firms.

This new reality of manufacturing development is addressed in this report by reviewing research conducted over the past year as part of the Small Scale Manufacturing Study, undertaken in conjunction with the North Atlantic Islands Program (NAIP). This research undertook an in-depth analysis of the global trends affecting manufacturing, a case analysis of sixty manufacturers in four jurisdictions (Newfoundland, PEI, Iceland and the Isle of Man), and a jurisdictional analysis of these four plus five additional distinct geographic areas. Large-scale manufacturing, with centrally-controlled branch plants, has not been the focus of this study. Neither were large-scale industrial operations, such as shipyards, oil refineries, mineral production plants or paper mills. These propulsive industries though, do create opportunities for small-scale manufacturers.

This report highlights the opportunities for locally-based small and medium sized firms which are entrepreneurial and which can build on local strengths while exploiting external opportunities. Increasingly, the relationships between firms are blurring, as small firms enter long-term contracts with large, sometimes multinational firms. Small-scale manufacturers, by learning and applying the latest management techniques and adopting new production and information technologies -

Abest practices@ - can create a competitive advantage which allows an export focus and which diminishes reliance on local raw material inputs. Access to local natural resources is still a strength to build on, but the basis of competitiveness is increasing the quality of human resources: management which has the ability to focus production, marketing and sales activities concentrated in those areas where the firm=s strengths can be best exploited, and the existence of a stable workforce with the skills to utilize the latest production techniques, implement quality processes and strive for continuous improvement and innovation. If small scale manufacturers can harness these strengths, distance from markets is no longer a barrier for many firms.This report highlights the global trends and best practices small-scale manufacturers must address to succeed. It reveals that many local firms are doing just that and are succeeding in the four island jurisdictions studied. The research also reveals

Abest practices@ for governments, industry associations, educators, and regional and community development organizations. If the small scale manufacturing sector is to grow and flourish in a jurisdiction, the institutions and organizations which support the efforts of individual firms and entrepreneurs must focus and coordinate their efforts. In Newfoundland and Labrador, government and industry have recognized the potential of small-scale manufacturing. The findings and strategies presented in this report build on current efforts to Amanufacture@ development in Newfoundland and Labrador.

2.0 Methodology

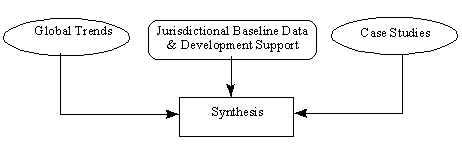

The study approach was three pronged as illustrated in Figure 1.

Each of the three study components, described in more detail in the following sections, was designed to provide distinct insights into manufacturing sector development. The Global Trends Study was initiated to identify and validate the general changes in manufacturing sector development, particularly for small-scale manufacturers. Concurrently, to understand the experiences of small scale manufacturers confronting these global trends, case studies of individual firms were carried out in four Aisland@ jurisdictions (cases in Labrador were included in addition to the island of Newfoundland). These studies allowed confirmation and clarification of the general global trends as they affect small-scale manufacturers in jurisdictions with relatively small populations and distant from major metropolitan centres. A third study on Jurisdictional Baseline Data and Development Support was then undertaken to compare the development of the sector in these four areas to an additional five jurisdictions, and to determine how the supports for manufacturing contributed to sector development.

This final report was prepared based on the analysis of the three studies, as well as other recent research and reports (see Appendix IV), to generate a strategy for sector development. Throughout the project an advisory committee, comprising industry, community, university, and government representatives (see Appendix I for listing) assisted in the analysis of findings and development of strategies.

The analysis of the global trends influencing small scale manufacturing entailed secondary research on the global environment by review of periodicals, journals, magazines, and other publications. Key informant interviews were also held in Newfoundland and Labrador to determine the prevalence and applicability of these trends and the impact on the manufacturing sector. The study began with research of information on outsourcing, private labelling, impacts of technology, just-in-time management systems, and total quality management. As the study progressed, research was broadened to include core competency and supply chain management. The findings of this research are discussed in Section 4.1.

2.2 Case Studies

Case studies in four island jurisdictions, undertaken in partnership with the North Atlantic Island

=s Program, were completed to gain insight into sector development in island economies. In total, 60 case studies were conducted, as follows:

Table 1 - Number of Cases Completed by Jurisdiction

Iceland |

Isle of Man |

Newfoundland & Labrador |

Prince Edward Island |

11 |

15 |

19 |

15 |

Companies were selected through consultation with jurisdictional key informants (see Appendix II) based on the following criteria:

Companies had to be small to medium in size. Of the 60 companies interviewed, 56 had less than 200 employees, with an average of 38. The remaining four had exhibited extraordinary growth over the last few years. These four companies were included in the qualitative analysis but were excluded from quantitative analysis to prevent skewing the results.

Companies had to be involved in secondary rather than primary processing.

Companies had to be non-resource-based, such that proximity to resource inputs was not key to the manufacturer=s competitive advantage.

An interview guideline was generated, with assistance from Dr. André Joyal, Université du Québec a Trois-Rivières. Dr. Joyal has significant experience in researching small scale manufacturers in rural Quebec. The intent of the interview guideline was, through closed - and open-ended questions, to determine the attributes of successful firms by questioning companies on such topics as success factors, initial and current challenges, role of technology, role of networking, and competitive strategies. A copy of the interview guideline is contained in Appendix III. Interviews were conducted from May to October 1997 by researchers from Newfoundland and Labrador, Iceland, and the Isle of Man.

The individual firm information was then transcribed into three-page synopses. Quantitative and qualitative data were also entered into a database to allow for analysis by such factors as jurisdiction, company size, and the use of technology. Case study findings are included in Section 3.2 of this report.

The Development Support Study was conducted to analyse the development of the sector in a range of jurisdictions, including what has been done in each to foster development. Baseline data and the analysis of government support for the manufacturing sector was carried out in: Prince Edward Island; Nova Scotia; New Brunswick; the Isle of Man; Iceland; Appalachia Region, Kentucky; Galway Region, Ireland; and North Bay Region, Ontario (see Figure 2 - Study Map).

Figure 2 - Study Map

These areas were included to provide a broad base for comparative analysis. Nova Scotia, New Brunswick, and Prince Edward Island were relevant comparisons given their proximity to and competitive position with Newfoundland and Labrador. The North Bay region was included as it is a resource dependent region within a central province in Canada. The Appalachian region of Kentucky was chosen for the same reason, but as it is in a state within the United States it enhanced analysis on the role of government. Iceland and the Isle of Man were included as they were both part of the North Atlantic Islands Program and provided additional insights into the significance of isolation and the role of government structures. Finally, Ireland was included as it is considered the leading jurisdictional success story on the North Atlantic rim in the past ten years. Research was conducted via secondary sources plus a combination of telephone and in-person interviews with key informants. The study involved the following components:

2.3.1. Jurisdictional Profiles

Jurisdictional profiles were developed and included information on geographic location, land mass, total gross domestic product, population, unemployment rates, and support structure.

2.3.2 Baseline Indicators

Where possible, baseline indicators showing overall economic and manufacturing development from 1987 to 1996 were gathered. Manufacturing employment and manufacturing

=s contribution to gross domestic product are examples of the indicators included. The indicators reported on in Section 3.3 have been limited to those which are comparable across jurisdictions when such factors as differing inflation, exchange rates, and purchasing powers are accounted for. An analysis of the trends arising in each jurisdiction, and possible causes for the trends and commentary regarding extraordinary events which may have impacted data, was then carried out.

2.3.3 Development Support Environment

This research included the following:

Identification and analysis of the broad government policy toward the manufacturing sector in each jurisdiction.

Identification and comparison of the supports in each jurisdiction for attracting and developing small scale manufacturers.

Trend review and consultation with jurisdictional contacts to assess the impact of the support environment on small scale manufacturing. This encompassed views on: jurisdictional trends; the existence and importance of industry support services; how these supports contributed to sector development; government's role in aiding manufacturing sector development; the impact of government cooperation and coordination on industry development; and whether the absence of particular supports limited development.

3.0 Study Findings

The Global Trends, Case and Base Line/Development Support Studies provide clear evidence that the changes occurring in manufacturing internationally are creating opportunities for entrepreneurs and firms in Newfoundland and Labrador. For manufacturers striving to enhance their competitiveness and for regions striving to foster manufacturing sector development, a common requirement emerges from the research - the need to focus. The key manufacturing trend globally, which is corroborated by the case studies of individual firms, is that successful manufacturers must focus on what they do best and market it better, rather than trying to produce anything for which there is a market. As will be discussed in Section 3.1 on Global Trends, manufacturers must determine their area of core competence and place greater emphasis on marketing what they do best. The case study findings described in Section 3.2 clearly demonstrate that the small scale manufacturers that do this sell more, export more and grow more.

The same applies to regions, be they a province, state or independent country. As detailed in Section 3.3, the jurisdictions which have experienced the most success in manufacturing development are those which have established and maintained a coordinated and sustained commitment to development and taken a strategic approach to identifying those sectors or activities for which the region has the best chance of success. For both firms and regions, globalization is the driving imperative to focus efforts. Global markets create enormous opportunities for those firms and regions that develop and maintain a competitive advantage, while global competition between firms and between regions and countries is sure to compromise those who do not focus on what they do best.

The following sections expand upon these findings and advance strategies for industry, labour, community development organizations, education and training institutions, and government.

3.1 Global Trends

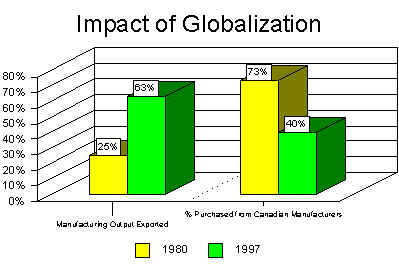

Globalization is having a major impact on manufacturing, both nationally and internationally. It creates new opportunities, yet at the same time exposes manufacturers to more competition. As an indication, in 1997, 65 percent of all goods manufactured in Canada were sold abroad as compared to only 25 percent in 1980 - a positive sign that Canadian manufacturers have done well in taking advantage of international opportunities. In turn, though, competition within the Canadian marketplace has increased. In 1980, for example, approximately 70 percent of the inputs purchased by Canadian manufacturers were manufactured by other Canadian companies. This decreased to 40 percent by 1997. This decrease was a result of Canadian companies realizing that in order to compete globally they have to source products from suppliers providing the best value - regardless of their geographic location. Hence, Canadian companies, while selling more product globally, also sourced increasing amounts of supplies internationally.

With globalization broadening the marketplace and increasing competition, customers are placing greater demands on manufacturers to increase quality while maintaining or lowering costs. If customers do not receive the value they desire in terms of delivery, quality, service, and price they shift to suppliers who can provide the package they desire. As transportation and communication linkages have improved, customers are no longer as limited by geography as they once were, nor compelled to deal with only mass manufacturers - they are more likely to seek out the most competitive manufacturers regardless of size or location.

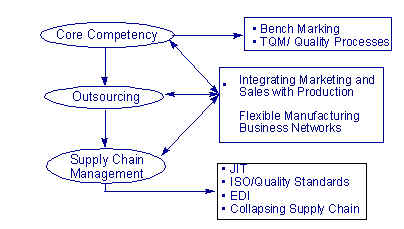

The impact of globalization on manufacturing and the associated trends and best practices are encapsulated in Figure 4. These are elaborated upon in the rest of this section.

The changes in manufacturing due to globalization are propelling a shift in business development strategy away from approaches that once emphasized vertical integration, where it was considered advantageous to try to control all aspects of the operation, such as a car manufacturer operating everything from iron ore mines to retail outlets. While this effort to internalize production dominated thinking for over 50 years, manufacturing firms now recognize that in order to compete in a global market a strategy of concentrating on doing a few things extremely well must be taken. This is commonly referred to as concentrating on a core competency. To achieve core competency, activities that are not done competitively are out-sourced or secured through partnerships, joint ventures, or strategic alliances with firms having the core competency. In manufacturing, bigger is no longer necessarily better.

One means of assessing core competency is to analyse the company=s value chain. A company=s operations can be broken into six broad activities (each with numerous sub-activities): research & development, business analysis, manufacturing, administration, marketing, and distribution. In assessing core competency, a firm should first determine which, if any, of these activities it does competitively. If none are done well, the company is not likely to survive over the longer term unless it embarks on a strategy to obtain a core competency. If it decides not to go the route of core competency, it may continue to enjoy success in the short term but, given increased competition from core competent firms, it will likely begin to lose customers as competitors are better able to meet customer demands in terms of price, quality, delivery, and service. To achieve core competency, the firm must decide, for each of the operational areas, to: adopt the tools necessary to become core competent; partner with core competent firms; or purchase products/services from core competent companies.

A case study which exemplifies the value of a core competency focus is that of an Isle of Man manufacturer of the undercarriage hydraulic valves which are used to control landing gear operation on airplanes. Five years ago the company manufactured the full undercarriage assembly but was losing ground to competitors. Management assessed the company and realized the company=s skill lay in the manufacturing of the hydraulic valve component and it was marginal in the other areas. The company then entered into a strategic alliance with another that had skill in undercarriage manufacturing, allowing it to concentrate on the development of hydraulic valves only. While sales decreased initially, they have since increased from that of five years ago, even though the company now operates with 40% less employees. The manufacturer contends that had it not refocused its efforts it would not be in operation today, and all of its 144 employees would have had to seek work elsewhere.

One technique for measuring and maintaining core competency is bench marking. Bench marking involves comparing a firm=s operations to the operations of other successful companies. Bench marking can range from comparing manufacturing processes of similar companies to learning from companies in completely different sectors. A famous example of the latter is Henry Ford=s discovery of assembly line production in meat packing plants, which he then used as basis for the production of automobiles. Bench marking identifies both measurement standards for comparison purposes as well as best practices which can be applied to the existing firm to improve competency.

In one Newfoundland case study, a company which manufactures mattresses for the import substitution market applied bench marking when designing its manufacturing plant. Before deciding on plant layout, company personnel arranged a tour of a well-managed manufacturing facility in another region. Permission was also obtained to bring along a video camera and this was then used by the plant manager to finalize the manufacturing set-up. In another example, a shoe manufacturer compared itself to its competition in terms of flexibility, turn around, and delivery time. Once the shoe manufacturer measured these, it was able to convince its main customer that it possessed advantages in all these areas, and was thus able to win back the customer from its lower cost, Asian competitors.

To ensure core competency is maintained and enhanced, and the needs of the customer are met, the concept of total quality management (TQM) can be incorporated into all aspects of a company=s operations. TQM is as much a management philosophy as a tool, in that management must commit to TQM and communicate to employees that quality assurance and improvement is crucial to the business operation. TQM then becomes a tool to ensure that all individual aspects of the business are managed and operated using a quality focus. If all components are managed using TQM, the likelihood of continuously maintaining and improving quality in a businesses product or service increases. Even where a full TQM approach is not adopted, a range of quality processes can be implemented to ensure that customer needs are constantly monitored and addressed.

The majority of companies interviewed recognized the importance of quality and the value a total quality management philosophy has within the organization. One such company is a PEI beverage manufacturer which refused to purchase lower quality ingredients when prices of high quality ingredients rose. The company chose not to follow the competition and lower standards, but rather to absorb the increased costs. While the company=s bottom line suffered for a couple of years, the company maintained its quality reputation and customer loyalty increased. When ingredient prices dropped and competitors reverted back to using the better ingredients, the company maintained its customer base.

Once a company identifies its core competencies, it can acquire other inputs, functions or services through out-sourcing. One Newfoundland company which recognises the value in out-sourcing is a casket manufacturer which purchases the rounded casket lids from another supplier because it takes a different process and skill level to manufacture this component. Another company which concentrates on core competency manufactures and markets only thermostatic controls for water heating devices such as electric kettles. The company, based in the Isle of Man, does the research, development and manufacturing associated directly with the thermostatic control but it does not manufacture wiring, heating coils, or any other component - rather it works with other suppliers as directed by customers such as Kenmore and Phillips. This company is considered the quality leader and customers rely on the company to provide quality control for all electronic components associated with the heating device. Due to the relationship it has developed with its customers and the reliance customers place on the company in terms of quality assurance, its growth has been phenomenal. This company now has a 75 percent world market share in thermostatic controls, employs 700 people, and has sales of over $120 million CDN. In 1980, it had less than forty employees and only five years ago sales were in the range of $40 million CDN.

Firms which focus on what they do best, rather that producing whatever they can sell, place greater emphasis on integrating marketing and sales with production. If they provide inputs to other firms, such as the producer of the rounded casket lids and the thermostatic control manufacturer in the examples above, their market lies in the production process of other manufacturers. On the other hand, companies which focus on both core competence and sales to the end user must ensure that marketing, sales and service effectively deliver the product of their core competence, since they have relinquished other potential income generating production through out-sourcing.

Flexible manufacturing is the way to minimize the risks of specialization. As will be discussed in Section 3.2, focussing on core competence seldom means manufacturing a single product. Rather, it means specializing in a particular type of product, a particular market niche or a specific manufacturing process. Flexible manufacturing enables the firm to apply its core competence to new product variations, to satisfy a market niche in new ways or to apply a production process to manufacture products for widely ranging markets. One PEI company produces a full range of products related to Ann of Green Gables - its core competence is in the market niche, not a specific product or process. An Icelandic metalworking company=s core competence is in the use of Computer Numerically Controlled (CNC) machining equipment. This allows high precision production that can be easily adapted for different products without high costs or long delays for re-tooling.

As small scale manufacturers focus on their own core competency, supplying other manufacturers with inputs or relying on other manufacturers for inputs which are then utilized for their own production, business networks become an additional means of minimizing the risks of specialization. Rather than enter into a market transaction every time they need an input, two or more firms with complementary core competencies establish on-going relationships. Business networks usually involve more than two firms, which form consortia or joint ventures to bid on projects or meet particular markets, or to cooperate in joint purchasing, share equipment or coordinate transportation. A high technology manufacturing firm in Newfoundland provided specialized assembly for a small light beacon attached to life jackets. The components were produced by two other firms and the product was owned and marketed by a fourth company. Such ongoing relationships require firms which not only have complementary core competencies, but which are also able to establish working relations founded on trust. The Asurvival-of-the-fittest@ spirit of free market competition must be tempered by an ability to collaborate, or else individual, specialized small firms are even more exposed to the challenges of global competitors.

Even where business networks are established, manufacturers who are linked in outsourcing relationships must become adept in supply chain management. The supply chain is the network of inter-connected firms which supply inputs to other firms which do further production or assembly and then market the product to the end user. Supply chain management increasingly involves a process of squeezing time and cost out of the supply chain. For small-scale manufacturers, careful monitoring and management of the supply chain is a critical success factor. Aiding supply chain management are various tools such as quality standards (eg. ISO 9000), electronic data interchange (EDI), and just-in-time (JIT) inventory systems. Quality standards enable companies in the supply chain to rely on each other. If one company depends on another as part of a global supply chain, it needs assurances that the inputs or products will arrive in time with the right quality. Electronic data interchange is the process of electronic data sharing amongst members of the supply chain. It is driven by technological improvements and is often critical to membership in the supply chain. Electronic data interchange allows such activities as automated ordering systems between the customer and manufacturer, integrated management information systems, quick exchange of electronic technical drawings and facilitates communication between members of the supply chain.

A Just-in-Time (JIT) inventory system is another tool that removes time from the supply chain while shifting risk and cost down to suppliers. With JIT, customer demand drives the ordering system and suppliers must react within a certain amount of time. The amount of time (lead time) is dependent on the type of customer and industry but can range from hours to weeks. If unable to guarantee delivery within the lead time, that manufacturer will not be able to secure contracts within that supply chain. Rather than the retailer carrying large inventories, all members of the supply chain carry only enough to satisfy demand during the lead time. This forces all supply chain members to share the inventory costs but reduces costs to the customer while improving delivery time. As the emphasis in manufacturing is more focussed now on the customer, a JIT system has become an integral tool in improving service while minimizing costs.

There are many examples of companies who are active in supply chain management. One Newfoundland company which is a sub-assembler of electronic components, arranged for a consignment warehouse near the customer to satisfy any concerns regarding delivery as the two companies were located 2500 kilometres from each other. A Prince Edward Island company which services the aerospace industry provides added value by arranging all transportation and paperwork for the customer. Another company, based in PEI, which manufacturers micro-brewery systems provides a full advisory service in terms of staff training, plant setup, and facility operation. This company also negotiates contracts with suppliers of raw materials (malt, hops, etc) for its customers.

A final trend is the collapsing supply chain. As firms merge and partner or take-over other firms, the market for many products is becoming more concentrated. The takeover of K-Mart by Zellers is a recent example. Outsourcing continues but there are fewer retail buyers. With increased buying power, retailers and other companies which supply products to the end user insist on fewer suppliers, who in turn manage supplier relationships with few sub-contractors. Companies are trying to minimize the time and cost of numerous transactions. They want longer-term relationships with a core group of quality-controlled, electronically integrated suppliers, thereby limiting access to the supply chain. This is prevalent in the food, apparel, and automobile industries, to name a few, and presents both greater rewards and risks for manufacturers as securing large contracts is more common but this increases the reliance by the manufacturer on fewer customers. This re-emphasizes the need for manufacturers to exercise supply chain management and to ensure continuous improvement in core competency to maintain competitive advantage.

One Isle of Man company that manufactures the heat transfer paper used to transfer print designs to fabrics recognized the collapsing supply chain and began offering design exclusivity to customers. Its competitors found it difficult to offer this service given that they were much larger and economies of scale did not allow it. A second Manx company, which manufactures computer keyboard covers, decided to by-pass the supply chain and sell directly to retail customers using a courier service. This company has nineteen employees and sales in excess of $2.3 million CDN, of which 70 percent are international. This is also an excellent example of a firm integrating sales and marketing with production.

For small-scale manufacturers these trends are not without risks. Many of the trends and related techniques identified in this study, such as out-sourcing, just-in-time, electronic data interchange, and supply chain management, are designed to cut time and costs from the production system, allowing the manufacturer to be the lowest cost producer in its product category. Suppliers must then cope with the demands of shorter lead times and the pressure to reduce costs or else risk being squeezed from the supply chain in lieu of a company which can cope with these demands.

If they are to compete successfully in this type of environment, manufacturers located in regions such as Newfoundland and Labrador must be aware of these downward pressures, be able to plan for them, and have the financial resources to meet them. To adopt management practices such as core competency, or to take advantage of opportunities such as out-sourcing or private-labeling as a business strategy, they must fully understand the implications such trends have for manufacturers located in peripheral locations. While issues such as transportation logistics and additional costs have become less of an obstacle, they have not disappeared completely, and are part of the business reality in which Newfoundland and Labrador manufacturers must operate.

To compensate for greater distances to market or the uncertainties of ferry transportation, companies who participate in just-in-time supply chains from island or remote locations often have to carry increased inventory for a variety of logistical and customer-driven reasons. In the case of Newfoundland and Labrador manufacturers who source supplies from out-of-province companies, they often have to over-stock raw material inventories to cover contingencies. In case of supplying into the chain, a Newfoundland manufacturer selling product into an Ontario-based just-in-time inventory system may be required to warehouse sufficient inventory in Ontario, so that the customer can be confident they will have a constant supply of product. Both these scenarios reflect the increased cost of doing business from remote locations.

Core competency attainment can lead to similar problems in finding and working with the right out-sourcing partner. If a Newfoundland manufacturer is concentrating on core competency and out-sourcing other aspects of the operation, it is likely that some of the out-sourced production will be completed by firms located in other parts of the country. This again has cost and transportation implications. There are economies of scale to be reached in out-sourcing, but this has cash flow implications for the business and can require additional working capital.

A third potential competitive disadvantage that peripherally-located firms often suffer is the inability to recognize and develop out-sourcing and private labeling opportunities. The processes of recognizing or creating the opportunity; developing a strategy to capitalize on it; finding the right partner or partners; developing the product; and getting it to market on time and at a competitive cost add up to be a complex undertaking. This can be particularly difficult for firms which have not traditionally operated in out-of-province markets. The costs of exploring these markets from peripheral locations is higher than from a central location close to the decision-makers and national buyers, usually in southern Ontario and Quebec.

While these disadvantages exist, they do not necessarily make operating from a peripheral region uncompetitive. In fact, peripheral firms have a number of advantages in terms of lower occupancy costs, stable labor force, and reduced labor costs that tend to balance the other extra costs of doing business from these areas. This was clearly shown in a recent KPMG study which outlined St. John=s as the lowest cost place to do business amongst 42 cities in North America and Europe.

Overall, given increased globalization and improvements in transportation and communication infrastructure , companies in peripheral regions can be viable, and often possess strategic advantages over their centrally- located competitors. Those that create competitive advantages and concentrate on core competency can compete in the global marketplace. Strategies are outlined in Section 4 to aid manufacturers in dealing with the challenges associated with operating from a peripheral area and are directed toward the continued development of core competent firms in Newfoundland and Labrador.

The results of the sixty case studies clearly demonstrate that the experience of the manufacturers studied verify the global trends identified through secondary research. It is important to note that the companies interviewed were not selected by a random sample, nor was the sample large enough to make statistical inferences. Firms were selected consistent with the criteria set out in Section 2.2, and within each jurisdiction a cross section of regions and sub-sectors was included. While not statistically representative of all firms in these jurisdictions, the results highlight practices and experiences which are common in the sixty firms studied and in the four island jurisdictions. Lessons can thus be generalized on the basis of this analysis to point to best practices from which the entire industry may benefit.

Table 2 provides a demographic profile of the companies studied.

Table 2 - Jurisdictional Overview

Category |

Iceland |

Isle of Man |

Newfoundland & Labrador |

Prince Edward Island |

Full Sample |

# of Firms |

11 |

15 |

19 |

15 |

60 |

Average Employees |

42 |

47 |

19 |

56 |

38 |

Employee Turnover |

9% |

8% |

5% |

5% |

7% |

Non-Jurisdictional Sales |

25% |

97% |

45% |

65% |

59% |

Past Growth |

10% |

9% |

18% |

21% |

15% |

Future Growth |

10% |

19% |

20% |

13% |

15% |

Age < 10 11 - 20 > 20 |

22% 11% 67% |

8% 46% 46% |

100% 0% 0% |

33% 33% 33% |

40% 29% 31% |

The average number of employees in the case study firms was 36, ranging from 19 in Newfoundland to 56 in Prince Edward Island. Employee turnover was relatively low at an average of 7% per year. The percentage of sales derived from outside the jurisdiction ranged from 25% in Iceland to 97% in the Isle of Man. Past growth averaged 15%, ranging from 9% in the Isle of Man to 21% in Prince Edward Island. Past growth was possibly higher for Newfoundland and Prince Edward Island as there were a greater proportion of younger firms interviewed in these jurisdictions and new firms would normally attain a higher annual percentage growth given that they are in the growth phase of the company life cycle.

Table 2 provides an overview of the case studies by jurisdiction. In conducting the case study analysis, emphasis was placed on determining what distinguished the more successful firms across all jurisdictions rather than doing jurisdictional comparisons, which would be limited due to insufficient sample size. Detailed financial data were not available to determine return on investment rates, but success could be measured based on sales per employee, growth and exports. In light of this, the primary determinant of competitiveness identified in the global trends study, core competency, was used as the basis for analysis. Determination of whether a manufacturer was concentrating on core competency was based on a review of responses to interview questions. Emphasis was placed on whether the company had identified its competitive advantages and success factors and whether it was focussed on a specific product type, market niche, and/or manufacturing process.

Core competent firms know what they do best and understand what is critical to the customer. They focus on being better than competitors in producing a particular product type, servicing a specific market niche, and/or using a particular manufacturing process. |

Other firms that did not have this specific focus took a more generalist approach to doing business. The generalist firms were more likely to go after various opportunities rather than ones that matched their specific strengths and advantages. In essence, generalist firms produce whatever they can sell rather than focussing on what they can do best and marketing that more effectively.

Thirty-eight of the sixty firms interviewed (63 percent) were considered to be concentrating on their core competency. This ranged from 27 percent of the Icelandic case studies to 80% of the companies interviewed from the Isle of Man and Prince Edward Island. As core competency appears critical for firms competing in global markets, given that the majority of the companies interviewed in the Isle of Man were export reliant whereas those interviewed in Iceland were more apt to sell in domestic markets, the differences in core competency between the companies interviewed in the two jurisdictions is not surprising. Of the nineteen companies interviewed in Newfoundland and Labrador, eleven or (58 percent) were considered core competent.

Strategic focus on core competence clearly enhances success. Table 3 shows the differences in the characteristics of core competent and generalist manufacturers. Sales per employee are greater for manufacturers that focus on core competency as is the percentage of non-jurisdictional sales. Both past growth and anticipated future growth were much higher for core-competent companies. Company age, though, was not a determinant of core competence as both core competent and generalist manufacturers were well dispersed within the categories of age. This suggests that core competency is more a function of management philosophy and strategy than age. The focus on core competency presents benefits in both sales and employment levels, in that the core competent firms are more likely to employ more people and attain higher sales levels as compared to generalists.

Table 3 - Type of Firm

Category |

Core Competent |

Generalist |

# of Firms |

38 |

22 |

Sales per Employee |

$135,000 |

$125,000 |

Employee Turnover |

6% |

7% |

Non-Jurisdictional Sales |

76% |

38% |

Past Growth |

20% |

6% |

Future Growth |

18% |

10% |

Age < 10 |

36% |

46% |

Employees < 10 |

13% |

36% |

Sales < 1 m |

17% |

40% |

The remaining analysis compares the core competent and generalist firms on a number of attributes. Tables 4 to 6 deal with differences between core competent firms and generalist firms concerning the adoption of technology, proactive market development and proactive product development. Tables 7 to 11 present the case study findings on how these firms access information and network with other firms, including trade show attendance, which also relates to marketing. All these factors relate to the broad but crucial area of innovation in business development. A recent Strategy for Enterprise in Ireland placed innovation as a central focus for manufacturing as

Ait is the key to profitable growth.@ The strategy notes that innovation includes all aspects of business operations and is not limited to technology, and that much innovation involves incremental continuous change rather than radical changes based on adoption of entirely new processes. A study of 500 medium to large scale manufacturing firms in the United Kingdom showed that, over a twelve-year period, the innovators averaged higher profits, higher growth and a market share of about five times the share of the non-innovators.Table 4 shows the differences in new information and manufacturing technology adoption between the two firm types. In the companies interviewed, technology use could be broken into four categories. Firstly, where the manufacturer did not use new technology in its business activities. Secondly, where the company used computer technology in the office to aid payroll, accounting, and other clerical functions. The third category is the use of new technology for the office and marketing functions. Examples of marketing technology include customer databases, management information systems, electronic ordering systems and web pages. The final category was the use of new office and marketing technology along with the use of relatively advanced technology in the production process. This could range from computerized machinery and electronic drafting software to robotics. Table 4 shows that almost half of the generalist companies do not use technology in either marketing or production functions. As outlined previously, the market is becoming more global and customers are demanding greater value from manufacturers. As a company=s ability to gather information, maintain customer service, improve product quality, and control costs is enhanced through technology, the lack of technology adoption by generalists is limiting their ability to compete globally.

Table 4 - Role of New Technology

Category |

Core Competent |

Generalist |

Do Not Use |

3.0% |

9.0% |

In Office Only |

5.0% |

38.0% |

Marketing/Office |

34.0% |

13.0% |

Market/Office/Prod |

58.0% |

40.0% |

Table 5 indicates that core-competent and generalist firms take a much different approach to marketing. The core competent firms were more likely to actively identify and research new markets. The generalist firms, were more reactive with respect to marketing. In light of the need to integrate marketing and sales with production, highlighted in the Global Trends study, it is clear that generalist firms focus on production, not on producing what they are best at and marketing it better.

Table 5 - Proactive Re: New Markets

Category |

Core Competent |

Generalist |

Reactive |

5.0% |

23.0% |

Average |

25.0% |

27.0% |

Proactive |

70.0% |

50.0% |

Core competent firms also ranked themselves high in ability to react to changes in the marketplace and to be flexible in terms of introducing new and modifying existing products, as shown in Table 6. This is important given the need for flexibility as outlined in the Global Trends study. These are also crucial elements for firms to be innovative. A focus on core competence requires bench marking and quality processes to proactively monitor and respond to changing production and market demands and opportunities. A core competent firm may not need to innovate in the short term to be profitable, but when faced with increased global competition and changing customer demands, only the innovative firm will keep ahead of the competition in the long term.

Table 6 -Ability to React to Changes in the Marketplace

Category |

Core Competent |

Generalist |

Slow to Adapt |

0% |

23% |

Average |

5% |

36% |

Fast to Adapt |

95% |

38% |

The manner by which firms gather information was also different for core competent versus generalist firms. Table 7 shows the different philosophy with respect to trade show attendance between the two groups. The interviews provided evidence that the core competent firms used trade shows strategically and as a source of competitor information whereas many generalists believed trade shows had little value and considered trade show participation detrimental, as competitors might learn about their company

=s products and operations.

Table 7 - Trade show Attendance

Category |

Core Competent |

Generalists |

Seldom Attend or Visit |

29% |

54% |

Visit/Display Some |

18% |

18% |

Show & Visit Regularly |

50% |

27% |

Table 8 illustrates the value placed on journals, magazines, and periodicals as a source of information. Once again, the core competent firms were more apt to gather information from external sources.

Table 8 - Information Source: Journals

Category |

Core Competent |

Generalists |

Poor |

17% |

62% |

Average |

19% |

10.% |

Good |

64% |

28% |

If generalist manufacturers relied on other firms for marketing and information their lack of pro-activeness in these areas would be less of an issue. Yet, as is indicated in Table 9, these firms are also less likely to partner with others. The core competent firms are more likely to be involved in formal networks which directly contribute to business operations such as joint ventures, partnerships, and strategic alliances. Generalist firms, in contrast, are more likely to avoid partnerships and participate in informal networking activities only. Once again, this is an important distinction given the role of networking in core competency attainment and managing supply chain opportunities.

Table 9 - Networking Activities

Category |

Core Competent |

Generalist |

None |

8% |

33% |

Informal Only |

36% |

28% |

Formal and Informal |

66% |

39% |

It is instructive to note that generalist firms place greater importance on industry associations as a source of information, as indicated in Table 10. Given this, associations are good avenues to supply relevant information to generalist firms.

Table 10 - Information Source: Associations

Category |

Core Competent |

Generalist |

Poor |

44% |

29% |

Average |

20% |

24% |

Good |

36% |

48% |

Generalist firms, though, place less value on government as a source of information as indicated in Table 11. This is not surprising as governments more often react to requests for information and since generalists are not information seekers, government would not be a good source. This differs from industry associations, as associations are more likely to forward general information to members.

Table 11 - Information Source: Government

Category |

Core Competent |

Generalist |

Poor |

39% |

53% |

Average |

33% |

29% |

Good |

28% |

18% |

The core-competent and generalist manufacturers also differ when making location selection decisions. As seen in Table 12, the core competent manufacturers are more likely to base decisions on business criteria such as access to markets, labour supply, access to inputs, and available assistance rather than non-business reasons such as lifestyle and long-term residency. This suggests that core competent manufacturers are more apt to be attracted to areas offering competitive advantages.

Table 12 - Rational for Location Decision

Category |

Core-Competent |

Generalist |

Business |

49% |

28% |

Assistance |

22% |

14% |

Non-Business |

29% |

58% |

With respect to current challenges, while there were many commonalities between the two groups, there were a few areas where the groups differed, as can be seen in Table 13. Core competent firms identified transportation and quality as an issue more often, which is not surprising given their focus on global markets. Generalist firms were more likely to identify capital as the major challenge. Once again this is not surprising given the different levels of success between core competent and generalist firms. Core competent firms have more resources because of their profitability and the business case is likely to be more attractive when seeking commercial financing.

Table 13 - Current Challenges

Category |

Core Competent |

Generalist |

Managing Growth |

22% |

17% |

Competition |

17% |

20% |

Securing HR |

15% |

9% |

Transportation |

13% |

3% |

Quality |

13% |

3% |

Working/Growth Capital |

7% |

27% |

Gathering Information |

7% |

3% |

Productivity |

3% |

6% |

Other |

3% |

12% |

The core competent and generalist firms also differed somewhat with respect to human resource issues. Core competent firms were less likely to identify any human resource problems, but when they did, the major problem identified was actually sourcing employees. Generalist firms, though, were more likely to identify other problems, such as staff turnover. Core competent firms place greater emphasis on human resources suited to a work environment requiring innovation and learning. On average, generalists do not require the same level of expertise and therefore would have fewer problems finding employees, but do not offer the opportunities for skills development and advancement in a growing business that helps keep employees. This was corroborated by the interviewers

= observations of the work environment and by other comments made by interviewees. As an example, one core competent firm in Newfoundland spent in excess of one year interviewing and hiring personnel to ensure they had the proper human resources upon which to build the company.In summary, the firms interviewed which showed greater success were those identified as being core competent. A jurisdiction wishing to develop its manufacturing sector would be wise to support the attraction and development of core competent firms. As indicated, core competency is not dependent on size, resources, or location but rather it is a function of the company

=s management ability, strategic focus, information utilization, and resource application. If a jurisdiction targets core competency in its programs and supports it can have significant impact on sector development. Evidence of this exists within the case studies from the Isle of Man given the prevalence of core competent firms in that jurisdiction. This is possibly due to its small local market which forced Manx companies to seek global opportunities rather than relying on import substitution. The Manx government recognized this and tailored its supports to enhancing global competitiveness. This has encouraged the development of technologically-able, market-oriented firms which view human resources as an integral component of the business operation. As is elaborated on in the next section, few other jurisdictions have employed such a targeted strategy.

The Development Support Study assessed nine jurisdictions to provide further lessons from the experience of similar maritime jurisdictions (Nova Scotia and New Brunswick), other resource-dependent regions in Canada and the United States (the North Bay region of Ontario and the Appalachian region of Kentucky) and the apparent success story of Ireland. Baseline data were gathered on the status of the economy and manufacturing in particular, as well as information on the way each jurisdiction supports manufacturing development. Some data were unavailable for the North Bay region and the Appalachian region, as they are sub-regions of a province and a state, but data are provided for both Ontario and Kentucky.

The research in all nine jurisdictions revealed that there is no obvious explanation for level of economic development based on location, population or other factors essentially out of the control of private and public sector actors. The political and economic powers harnessed to meet the needs of the region are significant, as are cultural and traditional approaches to education and cooperation in the society. Factors involving specific conditions required for manufacturing sector development are available to all jurisdictions: having a coordinated and sustained commitment to sector development; taking a strategic approach; and harnessing partnerships and champions for strategy development/implementation. All jurisdictions have essentially the same range of business supports and no particular program or financial incentive can be seen as decisive in the development of the sector - there are no

Asilver bullets.@ Increasingly, nonetheless, the more successful jurisdictions are gearing the range of supports to address the emerging trends in manufacturing. These jurisdictional Abest practices@ are outlined in the following sections.

Table 2 provides a jurisdictional overview showing the general strength and performance of each economy over the past ten years. From this, inferences are made as to the jurisdictions successful in spurring general economic and specific manufacturing sector growth. It is important to note that the jurisdictions studied varied in terms of size and government structure, which helped to isolate factors contributing or impeding sector development across the jurisdictions. In addition to the four NAIP islands, this section includes statistical comparisons with the other Atlantic Canadian provinces as well as Ontario, Kentucky and Ireland. This enables a broader consideration of the relative success of sector development, as small island economies are often dismissed as unable to provide the basis for competitive success. The analysis of how jurisdictional authority, resources and strategy are used in supporting sector development also draws on this broader comparative analysis to assist in delineating the general jurisdictional

Abest practices@ and those which indicate the unique advantages or disadvantages of island jurisdictions.

When reviewing general economic strength Iceland, the Isle of Man, Kentucky, and Ontario have to be highlighted given their low unemployment rates and high GDP per capita. In terms of overall economic growth, Ireland

=s 5.0 percent, the Isle of Man=s 5.3 percent, and Kentucky=s 3.1 percent annual growth rates stood out when compared to the other jurisdictions. Much of this growth was driven by expansion in the manufacturing sector, especially in Ireland and Kentucky as in these jurisdictions growth in the manufacturing sector outpaced overall economic growth. This sector growth was largely achieved through productivity improvements.Ireland

=s growth has yet to produce the low unemployment and high economic output as compared to the other jurisdictions but remains remarkable given that Ireland was one of Europe=s least developed economies a decade ago. The Kentucky experience should be viewed as a indication of the strength associated with an economy built on manufacturing. The state of the Irish, Kentucky and Ontario economies must be qualified by the fact there are significant regional disparities within each jurisdiction which are not indicated by aggregate statistics. Many rural areas within these jurisdictions still lag in terms of development. The Isle of Man=s performance proves that small, peripheral economies can outperform larger, central economies.Newfoundland & Labrador holds similar promise if current trends can be built upon. In the past two years the manufacturing sector

=s contribution to the provincial economy has grown by more than 20 percent and in 1998 the industry accounted for over 17000 "full-time, equivalent@ jobs. Growth is occurring in areas the province has traditionally had strength, such as in fish processing and newsprint. These two sectors have experienced combined employment growth of approximately 15 percent since 1996 and account for 50 percent of the provincial manufacturing sector. Growth is also occurring in areas in which provincial companies are acquiring new core competencies such as in manufacturing recreational vehicles, marine animal tracking equipment, windows, metal fabrication and electrical products. There are now over 800 manufacturing companies in the province, 20 percent more than in 1994, manufacturing and selling products within the province, across Canada, and throughout the world.

Table 2 - Jurisdictional Profiles

Category |

NF |

ICE |

IoM |

IRE |

KEN |

NB |

NS |

Ont |

PEI |

Overview |

|||||||||

> 96 Pop. (000's) |

560 |

270 |

72 |

3567 |

3857 |

753 |

931 |

11100 |

136 |

Land (000's km2) |

390 |

103 |

1.5 |

70 |

103 |

70 |

54 |

1067 |

5.5 |

Gov. Form |

Prov. |

Rep. |

CD |

Rep. |

State |

Prov. |

Prov. |

Prov. |

Prov. |

1996 Status |

|||||||||

Unemployment Rate |

18.8% |

3.9% |

2.8% |

13.5% |

5.6% |

12.8% |

12.2% |

8.5% |

14.9% |

Manufacturing % of GDP |

7% |

17% |

10% |

35% |

30% |

14% |

12% |

25% |

9% |

Per Capita GDP |

17979 |

28355 |

23445 |

23165 |

30179 |

21385 |

20221 |

29101 |

19470 |

86-96 Growth |

|||||||||

GDP |

1.5% |

1.6% |

5.3% |

5.0% |

3.1% |

2.1% |

1.3% |

1.9% |

2.7% |

Manufacturing Sector Overall |

-1.2% |

-0.3% |

2.5% |

6.4% |

3.9% |

1.9% |

0.3% |

1.5% |

6.2% |

Manufacturing Employment |

-4.4% |

-1.3% |

0.5% |

1.9% |

2.0% |

0.6% |

-1.4% |

-1.0% |

4.0% |

Manufacturing Labour Productivity |

3.2% |

1.0% |

2.0% |

4.4% |

1.8% |

1.3% |

1.7% |

2.5% |

2.1% |

It is clear that, individually, government form, location, land mass, economic strength, and population size do not predetermine sector growth. When jurisdictions as different as Kentucky, Ireland and the Isle of Man can experience success it is obvious that it results from a combination of factors. The indicators presented provide both an overall appreciation of the context within which manufacturers operate and an understanding of the manufacturing status within the respective jurisdictions. They do not provide a clear understanding of how small-scale manufacturers have fared, nor do they assist in discerning what factors have contributed to manufacturing development. To determine this, the Development Support Environment in each jurisdiction was reviewed.

3.3.2 Development Support Environment

The economic indicators for each of the jurisdictions studied provide an overall appreciation of the context within which small-scale manufacturers operate. The statistics on manufacturing provide an understanding of the status of all manufacturing in the respective jurisdictions, including large-scale as well as small-scale manufacturing.

To understand what factors have contributed to small-scale manufacturing development in these jurisdictions, government and industry publications were reviewed from each and site visits were made to interview key informants from the private, public and community sectors. From this research five key aspects of the development support environment emerged as crucial components for the development of the sector. No one jurisdiction can be considered to have them all

Aright@, and indeed, what is the right way to manage them in one jurisdiction may not be appropriate in another. It is clear that maximizing the opportunities for sector development requires each of the five to be considered and comparing how they are approached across these jurisdictions can be seen as a form of Adevelopment support benchmarking.@The five components to consider in shaping the development support environment are:

1) Supportive Socio-Economic Environment;

2) Coordinated and Sustained Commitment to Sector Development;

3) Strategic Approach;

4) Partnerships and Champions for Implementation;

5) Business Supports for Best Practices.These components constitute a continuum of interventions, from the very macro to firm-specific micro supports. All these factors effect the ability to develop the manufacturing sector. As the review of these factors will reveal, applying these

Ajurisdictional best practices@ requires adaptation to the specific conditions of each location. There is no template for economic development that can be universally applied. There are lessons, however, which will contribute to manufacturing development if applied in manner complementary to the specific conditions in each location.This section will draw from the review of the nine jurisdictions to outline these best practices. It does not provide a comprehensive listing of how each jurisdiction applies - or fails to apply - each type of intervention. The background research reports for this study and government and industry publications from each location provided this detailed accounting. The intent here is to highlight the elements of a successful manufacturing development strategy by drawing on this research. For Newfoundland and Labrador, and for any jurisdiction wanting to maximize the contribution of the manufacturing sector in its economy, these best practices must be understood and, as much as possible, harnessed.

Supportive Socio-Economic Environment

The socio-economic environment is largely a given in the short to medium term for a specific jurisdiction, but the characteristics of a society or the governance structure have profound impacts on the development of specific economic sectors. These characteristics must be taken into account when trying to apply lessons from one location to another. Applying lessons from Ireland or Iceland to Newfoundland and Labrador, for example, must take into account the different tools at the disposal of an independent country compared to a province, as well as differences in culture and attitudes. The socio-economic environment must also be considered when conducting the environmental scan which forms an initial component of strategic planning (discussed in more detail below). Finally, to the extent that governments, citizens or community or sectoral organizations can influence the broad context of their society, it is important to understand what factors contribute to long-term economic development.

As noted, the organization of government in a jurisdiction has profound impact on what tools are available to support economic development in general, or the development of a specific sector. Iceland has proven that a small population in a remote region can foster a prosperous society by building on their resource base. This has been focussed primarily on the fishery in Iceland, both in terms of its management and development. As a nation, even with just 270,000 people, Iceland exercised its sovereignty in opposing foreign over-fishing in the 1970s.